Importance

Anterior

cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are amongst the most common season

or career ending knee injuries for athletes. Unfortunately, ACL

injuries can impact the athlete both emotionally and psychologically

in addition to the obvious physical limitations they place on

training and performance. However, the economic implications of ACL

injuries in the United States are as staggering as they are

overlooked. ACL patients requiring surgery account for 1.5 billion

dollars annually in health care costs (1). Physical therapists and

coaches must be attentive in their design of practices and strength

training routines to include exercises that can help to prevent ACL

injuries if only to keep their athletes healthy and happy. However,

it is imperative that preventative measures are taken with female

athletes for reasons beyond keeping them healthy and happy. Female

athletes are four to six times more likely to injure the ACL than

males (1, 2). As a result, females account for a huge portion of the

1.5 billion dollars in health care costs associated with ACL

injuries mentioned earlier. The best treatment for an ACL injury is

prevention. Studies have shown that prevention programs focused on

neuromuscular training and proprioceptive training decreases the

risk for an athlete 3.6-3.7 times than the control groups (1, 3).

Physical therapists play a large role in the development of these

programs and the ability to rehabilitate athletes from any type of

knee injury while decreasing the risk of ACL injuries.

Anterior

cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are amongst the most common season

or career ending knee injuries for athletes. Unfortunately, ACL

injuries can impact the athlete both emotionally and psychologically

in addition to the obvious physical limitations they place on

training and performance. However, the economic implications of ACL

injuries in the United States are as staggering as they are

overlooked. ACL patients requiring surgery account for 1.5 billion

dollars annually in health care costs (1). Physical therapists and

coaches must be attentive in their design of practices and strength

training routines to include exercises that can help to prevent ACL

injuries if only to keep their athletes healthy and happy. However,

it is imperative that preventative measures are taken with female

athletes for reasons beyond keeping them healthy and happy. Female

athletes are four to six times more likely to injure the ACL than

males (1, 2). As a result, females account for a huge portion of the

1.5 billion dollars in health care costs associated with ACL

injuries mentioned earlier. The best treatment for an ACL injury is

prevention. Studies have shown that prevention programs focused on

neuromuscular training and proprioceptive training decreases the

risk for an athlete 3.6-3.7 times than the control groups (1, 3).

Physical therapists play a large role in the development of these

programs and the ability to rehabilitate athletes from any type of

knee injury while decreasing the risk of ACL injuries.

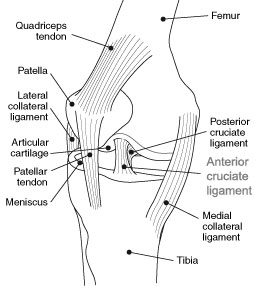

Anatomy

The anatomy of the ACL and the surrounding structures is an

important factor to consider when developing programs to prevent ACL

injuries in athletes. Female athletes have a greater Q angle than

males, which increases the amount of valgus forces at the knee

creating an unstable mechanism (1, 4). The main function of the ACL

is to decelerate the lower extremity with movement as the tibia

internally rotates and the hip internally rotates (4). This is

extremely important in the athletic setting because any weakness

during eccentric loading of the lower extremity forces increased

strain on the ACL by increasing the load on the ACL (4). Individuals

with a high risk of ACL injuries are typically in a position where

the pelvis and hip are uncontrolled. This lack of control over the

pelvis and hip put the hip abductors and extensors at a disadvantage

and eventually force these muscles to shut down (3).

The anatomy of the ACL and the surrounding structures is an

important factor to consider when developing programs to prevent ACL

injuries in athletes. Female athletes have a greater Q angle than

males, which increases the amount of valgus forces at the knee

creating an unstable mechanism (1, 4). The main function of the ACL

is to decelerate the lower extremity with movement as the tibia

internally rotates and the hip internally rotates (4). This is

extremely important in the athletic setting because any weakness

during eccentric loading of the lower extremity forces increased

strain on the ACL by increasing the load on the ACL (4). Individuals

with a high risk of ACL injuries are typically in a position where

the pelvis and hip are uncontrolled. This lack of control over the

pelvis and hip put the hip abductors and extensors at a disadvantage

and eventually force these muscles to shut down (3).

Seventy percent of all ACL injuries are noncontact (4) and the

mechanism of injury is as follows: relatively little flexion, with

hip internal rotation and adduction on a pronated and externally

rotated foot (4). As you can see, many ACL injuries involve not only

the biomechanics of the knee but those of the hip and ankle as well.

Neuromuscular programs have been developed to improve the stability

of the lower extremity with functional close chain exercises at the

hip, knee, and ankle.

Prevention

Evidence supports the need for neuromuscular and proprioceptive

retraining for the prevention of ACL injuries. Stability training

helps to improve the athlete’s ability to co-contract the lower

extremity. Additionally, stability training has proven instrumental

in providing proprioceptive feedback with unpredictable dynamic

activity (2). A study by Paterno et al concluded that a six week

neuromuscular training program being utilized three days per week

improved total anterior/posterior postural stability in young female

athletes (4).

A comprehensive neuromuscular program was described in the article

by Paterno. The focus of the preventative program for female

athletes included three subgroups. The first subgroup included

female athletes engaging in balance training and hip, pelvis, and

trunk strengthening. The second subgroup included female athletes

engaging in plyometrics and dynamic movement training. The final

subgroup included female athletes engaging in resistance training.

This study shows that participation in all three groups over a six

week period; postural and stability changes occurred. With this

evidence, it is important for all therapists and coaches to

education themselves on proper form and corrections for athletes to

minimize their risk of injury. The importance of ACL prevention

programs is to educate the athlete on safe positions, proper

posture, and the ability for the athlete to self-correct.

Proprioceptive retraining is important with all dynamic

sport-related maneuvers. Cutting, jumping, and quick start and stop

motions are of particular importance during proprioceptive

retraining. Prevention programs focus on completing these activities

with proper biomechanics. All close chain functional activities

should be performed using methods to minimize the amount of stress

placed on the body. An example would be proper jumping mechanics.

Each athlete must land on the balls of their feet before

transferring their weight to their heels. Athletes should also be

required to land with bent knees and their center of gravity shifted

forward (1). Additional cues with which to provide the athlete

include having a soft landing with toe to heel rocking in order to

decrease the ground reaction forces (1). Many athletes, specifically

females, tend to perform plyometric activities in a more upright

position. This creates greater force on the knee and maximizes the

anterior shear forces of the quad. Ultimately, these greater forces

combine to increase the total load on the knee which can lead to ACL

injury (1). Proper verbal cuing is important to maximize the benefit

of the neuromuscular retraining and begin to teach the athlete how

to self-correct.

In conclusion, the evidence mentioned above supports the need for

proper training and education for therapists, athletes, and coaches

to minimize the risk of season ending knee injuries. Without the

proper stability training, postural cuing, and education, athletes

will continue to fall into poor biomechanics and increase the load

and stress on the ACL. With the proper education, many noncontact

ACL injuries can be prevented allowing athletes to have successful

and accomplished seasons.

Last revised: November 14, 2010

by Elisa Suchy, DPT

References:

1) Boden, BP, Griffin LY, et al.

Etiology and Prevention of Noncontact ACL Injury. The Physician and Sports

Medicine. 2000;28.

2) Paterno, M et al. Neuromuscular Training Improves Single-Limb Stability

in Young Female Athletes. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical

Therapy. 2004;34:305-316.

3) Ireland, M. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury in Female Athetes:

Epidemiology. Journal of Athletic Training 1999;34:150-154.

4) Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate

ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. JournalA of the

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000;8:141-150.

Anterior

cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are amongst the most common season

or career ending knee injuries for athletes. Unfortunately, ACL

injuries can impact the athlete both emotionally and psychologically

in addition to the obvious physical limitations they place on

training and performance. However, the economic implications of ACL

injuries in the United States are as staggering as they are

overlooked. ACL patients requiring surgery account for 1.5 billion

dollars annually in health care costs (1). Physical therapists and

coaches must be attentive in their design of practices and strength

training routines to include exercises that can help to prevent ACL

injuries if only to keep their athletes healthy and happy. However,

it is imperative that preventative measures are taken with female

athletes for reasons beyond keeping them healthy and happy. Female

athletes are four to six times more likely to injure the ACL than

males (1, 2). As a result, females account for a huge portion of the

1.5 billion dollars in health care costs associated with ACL

injuries mentioned earlier. The best treatment for an ACL injury is

prevention. Studies have shown that prevention programs focused on

neuromuscular training and proprioceptive training decreases the

risk for an athlete 3.6-3.7 times than the control groups (1, 3).

Physical therapists play a large role in the development of these

programs and the ability to rehabilitate athletes from any type of

knee injury while decreasing the risk of ACL injuries.

Anterior

cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are amongst the most common season

or career ending knee injuries for athletes. Unfortunately, ACL

injuries can impact the athlete both emotionally and psychologically

in addition to the obvious physical limitations they place on

training and performance. However, the economic implications of ACL

injuries in the United States are as staggering as they are

overlooked. ACL patients requiring surgery account for 1.5 billion

dollars annually in health care costs (1). Physical therapists and

coaches must be attentive in their design of practices and strength

training routines to include exercises that can help to prevent ACL

injuries if only to keep their athletes healthy and happy. However,

it is imperative that preventative measures are taken with female

athletes for reasons beyond keeping them healthy and happy. Female

athletes are four to six times more likely to injure the ACL than

males (1, 2). As a result, females account for a huge portion of the

1.5 billion dollars in health care costs associated with ACL

injuries mentioned earlier. The best treatment for an ACL injury is

prevention. Studies have shown that prevention programs focused on

neuromuscular training and proprioceptive training decreases the

risk for an athlete 3.6-3.7 times than the control groups (1, 3).

Physical therapists play a large role in the development of these

programs and the ability to rehabilitate athletes from any type of

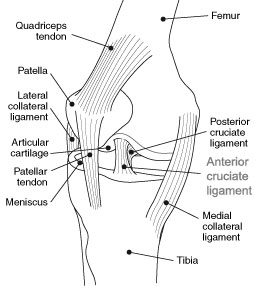

knee injury while decreasing the risk of ACL injuries. The anatomy of the ACL and the surrounding structures is an

important factor to consider when developing programs to prevent ACL

injuries in athletes. Female athletes have a greater Q angle than

males, which increases the amount of valgus forces at the knee

creating an unstable mechanism (1, 4). The main function of the ACL

is to decelerate the lower extremity with movement as the tibia

internally rotates and the hip internally rotates (4). This is

extremely important in the athletic setting because any weakness

during eccentric loading of the lower extremity forces increased

strain on the ACL by increasing the load on the ACL (4). Individuals

with a high risk of ACL injuries are typically in a position where

the pelvis and hip are uncontrolled. This lack of control over the

pelvis and hip put the hip abductors and extensors at a disadvantage

and eventually force these muscles to shut down (3).

The anatomy of the ACL and the surrounding structures is an

important factor to consider when developing programs to prevent ACL

injuries in athletes. Female athletes have a greater Q angle than

males, which increases the amount of valgus forces at the knee

creating an unstable mechanism (1, 4). The main function of the ACL

is to decelerate the lower extremity with movement as the tibia

internally rotates and the hip internally rotates (4). This is

extremely important in the athletic setting because any weakness

during eccentric loading of the lower extremity forces increased

strain on the ACL by increasing the load on the ACL (4). Individuals

with a high risk of ACL injuries are typically in a position where

the pelvis and hip are uncontrolled. This lack of control over the

pelvis and hip put the hip abductors and extensors at a disadvantage

and eventually force these muscles to shut down (3).