|

PT Classroom - Implications For Treating Post Surgical Shoulder Patients ׀ by Chai Rasavong, MPT, MBA |

||||

|

The shoulder complex is an area which is commonly treated by physical therapists. In some circumstance patients don't improve despite participation in physical therapy and compliance with a home exercise program. When this is the case, the patient is often referred back to the physician or an orthopaedic surgeon for further medical attention. Medical imaging techniques such as a X-Ray, CT scan, MRI or arthrogram can be conducted to help determine the etiology at the shoulder. Through medical imaging it can be determined if a patient has involvement at various structures such as the labrum, biceps tendon, bursa(s), joint(s), rotator cuff or ligament(s). Should imaging display involvement at a structure, surgical intervention may be required in order to help the patient achieve optimal outcomes. This article addresses some of the more common surgical interventions for the shoulder and the implications for treating the post surgical shoulder patient based on the surgical intervention.

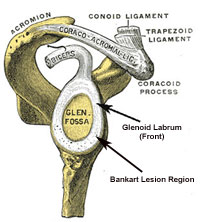

The glenohumeral joint has intrinsic laxity, restrained by a careful balance of static and dynamic stabilizers (1). The chief static stabilizers are the glenohumeral ligaments and labrum (2). A Bankart lesion usually occurs with an anterior dislocation of the shoulder which can result in a tear of the anterior/inferior aspect of the labrum. Surgery is often indicated for patients who have irreducible dislocations, displaced tuberoisty fractures, glenoid rim fractures, instability during rest/sleep or for a patient that experiences 3 or more dislocations a year (3).

Bankart Repair Repair of a Bankart lesion can be performed utilizing an arthroscopic procedure or an open procedure. An arthroscopic procedure doesn't involve detachment of muscles and usually results in a faster recovery time. Emphasis is stressed to protect the repaired labrum. An open procedure usually requires the detachment and reattachment of the subscapularis. Recovery from this surgery is slow and requires protection for both the labrum and subscapularis. Usually AROM for internal rotation is not recommended until 3-4 weeks (4).

Physical therapy treatment after an arthroscopic Bankart repair can, in most cases, include isometrics, rhythmic stabilization, and elbow/wrist/hand strengthening exercises. Emphasis is placed on protecting the anterior/inferior labrum repair (NO AROM IR for 4 weeks & LIMIT PROM ER) (3). A sample protocol for informational purposes only of a Bankart repair can be reviewed by clicking on: Bankart Repair Protocol

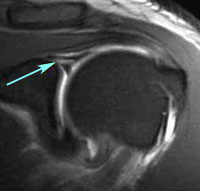

A SLAP tear usually occurs as a result of a dislocation or repetitive subluxations at the glenohumeral joint. It is not isolated to just anterior dislocations like the Bankart lesion. The long head of the biceps tendon is usually involved and this injury can occur with overhead throwing activities secondary to the biceps long head tendon acting as an accelerator and decelerator of the arm (5). SLAP lesions can be categorized into four categories: Type 1: Fraying of superior labrum but biceps attachment to labrum is attached Type II: Biceps-superior anchor has pulled away from the glenoid Type III: Bucket-handle tear of the superior labrum with intact biceps arch Type IV: Bucket handle tear extending into the biceps tendon (6)

SLAP Repair

Repair of a SLAP lesion is usually performed arthroscopically unless the biceps is severely torn. Depending on the type of SLAP lesion which is repaired, rehabilitation will vary. For a type I and Type III SLAP repair the biceps attachment is relatively intact and progression will be slow beginning with PROM and progressing to AAROM. For a Type II and IV SLAP repair, the rehabilitation regime is more conservative because the bicep tendon is significantly damaged and may not have a good attachment (3). Protection of the superior labrum is of utmost importance with the limitation of biceps activity, the limitation of external rotation beyond neutral and extension of the arm behind the body with the elbow extended (3). Sample protocols for informational purposes only of Type I & III and Type II & IV SLAP repairs can be reviewed by clicking on: SLAP Type I & III Repair and SLAP Type II & IV Repair

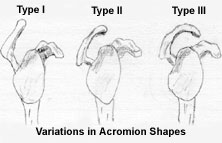

Some patients are predisposed to an impingement syndrome because of the type of acromion they possess. Type II and III acromions are more hooked and result in an increase likelihood of an impingement dysfunction (7). A subacromial decompression is performed to correct for an impaingement syndrome. It involves shaving away part of the acromion bone, removal of the coracoacromial ligament and subacromial bursa. Often times a distal clavicle resection (DCR) may be performed as well to create additional space.

Rehabilitation after a subacromial decompression is fairly basic (8). The patient is usually progressed as tolerated with a slow increase in abduction with ER (4). Strengthening can usually begin early on in rehab. Cross body adduction is usually not performed until 8 weeks (3). In the early stages of rehab scapular movement should be minimized because of the excessive AC joint work performed (3). A sample protocol for informational purposes only of a subacromial decompression can be reviewed by clicking on: Subacromial Decompression

The rotator cuff has 4 main functions: 1) rotation of the humeral head 2) stabilization of the humeral head in the glenoid socket by compressing the round head into the shallow socket 3) provides "muscular balance" stabilizing the GH joint when other larger muscles crossing the shoulder contract 4) depresses the humeral head during overhead activities (3). The etiology of rotator cuff tears can be attributed to one or a combination of the following: repetitive microtrauma, disuse, overuse tendinitis, anatomic factors, and attrition (4). Of the four tendons comprising the rotator cuff, the supraspinatus tendon is most commonly torn as this tendon often corresponds to the site of subacromial impingement. A rotator cuff tear can be classified as either a partial tear or a complete tear. A partial tear appears as fraying on an intact tendon while a complete tear is an actual tear to one of the four tendons comprising the rotator cuff. Complete tears can be further classified based on the size of the tear: Type I (small): 0-1 cm, Type II (medium): 1-3 cm, Type III (large): 3-5 cm, Type IV: >5 cm.

Rotator Cuff Repair There are many factors which should be taken into consideration prior to treating a patient who is post surgical rotator cuff repair. Such factors can include: 1) type/size of tear 2) rotator cuff muscles involved: ie. tears that involve the posterior cuff structures require slower progression in ER strengthening while tears that involve the anterior structure (subscapularis) requires limited resisted IR for 4-6 weeks 3) tissue quality - thin or weak tissue is progressed slower than good quality tissue 4) patient variables - age, smoker, pre-injury level, desired outcome (work or sports), work situation (3). Sample protocols for informational purposes only of Type I, II and III rotator cuff repairs can be reviewed by clicking on: Rotator Cuff Repair Type I (<1 cm), Rotator Cuff Repair Type II (1-3 cm), Rotator Cuff Repair Type III (<3-5 cm)

Last revised: August 5, 2008

References |

|

|

|

|